Gary Eldred: In our last conversation, Rick, we suggested that investors differ from speculators. Can you contrast these two approaches to asset allocation.

Rick Dryer: That’s a good question. Essentially, we return to probabilities. If the evidence indicates that that there’s an 80, 90, maybe even a 95 percent certainty that your acquisition will pay off profitably, you’re investing. If you bet long odds, if you choose to ignore or go against the evidence, you’re speculating.

Gary Eldred: Okay, sounds good. But how do you judge probabilities?

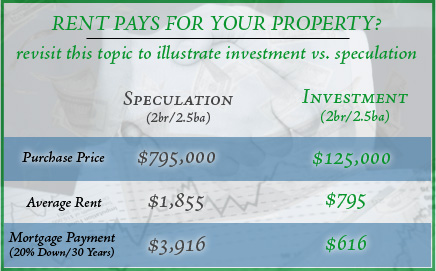

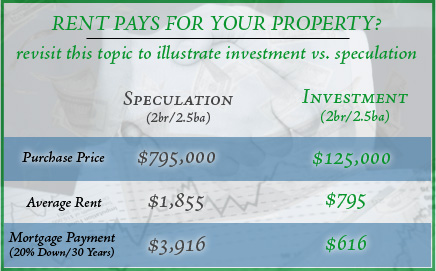

Rick Dryer: In a word, cash flow. As we have mentioned previously, if the reasonably expected cash flow supports the price you pay for the asset, you’re investing. If the reasonably expected cash flow does not support the asset price, you’re speculating.

Gary Eldred: All of those “reasonablys” makes you sound like a lawyer. Give me an example.

Rick Dryer: That’s easy. If over time, your rents cover the property’s operating expenses and mortgage payments, you’re investing. The key is, over time. Nothing wrong in buying properties that have a little negative cash flow on acquisition with aggressive leveraging; which means, of course, a big mortgage, to increase returns from appreciation. Gently rising rents over time should handle that. But, if as in California or New York, your rents barely cover fifty or sixty percent of your monthly outlays, you’re speculating.

Gary Eldred: You would make John Burr Williams proud.

Rick Dryer: Who?

Gary Eldred: John Burr Williams wrote the classic discussion of investing in his 1938 book, The Theory of Investment Value, published by Harvard University Press. Here’s a quote from Williams that I used in my book, Value Investing in Real Estate.

Every thoughtful investor knows that he should not confuse the real worth [intrinsic value] of an investment with its market price. No buyer considers all investments equally attractive. . . . On the contrary, he seeks “the best at the price.” He picks and chooses among all possibilities. Even then, he may not buy at all, for fear that everything is priced too high and nothing will give him his money’s worth.

If he does buy, and buys as an investor, he holds for income; if as a speculator, for profit at sale. But [over the long run] speculators can profit only by selling to investors [i.e., those who value income]; therefore in the end, all investment values depend on someone’s estimate of future income. [Of course] investors differ in their estimates . . . [Thus], our problem is twofold: (1) to explain the market price as it is, and to show how to calculate the investment value as it should be.

Rick Dryer: With some refinements, that quote pretty much sums up my investing philosophy. If you merely hope someone will pay you a higher price than you paid

for the asset—without regard to the amount of income the asset can reasonably be expected to produce over time—you are playing the “greater fool’ game.”

Gary Eldred: In terms of adding to the John Burr Williams passage, I’ll bet you want to put more emphasis on the growth potential of the asset’s cash flows.

Rick Dryer: Exactly. If you only focus on the amount of current cash flows relative to price, you could end up buying properties in a place like Terre Haute—no offense.

Gary Eldred: None taken. Remember, I sold Terre Haute even though my properties cash flowed like a slot machine. Cash flow is an indicator in the “zone” so to speak, but just one indicator. What you call “up indicators” are even more important.

Rick Dryer: Right you are. As you know, Gary, properties in areas such as Terre Haute don’t quickly appreciate because the population demographics and job base aren’t growing. With weak growth in the economic base of an area, you can’t raise your rents much more than the rate of inflation—and maybe not even enough to match increases in the CPI. The “up indicators” are not there in my opinion

Gary Eldred: Right. Although you make big money from appreciation, you need cash flow growth to support those price increases. When prices jump without much growth in cash, you’ll generally find speculators create that disparity between income and price.

Rick Dryer: Speculators play the greater fool game. They think that they can always find a greater fool who will pay a price higher than they paid regardless of the amount of income.

With weak growth, you can’t raise

your rents much more than the

rate of inflation.

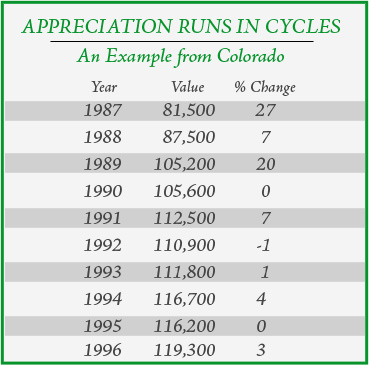

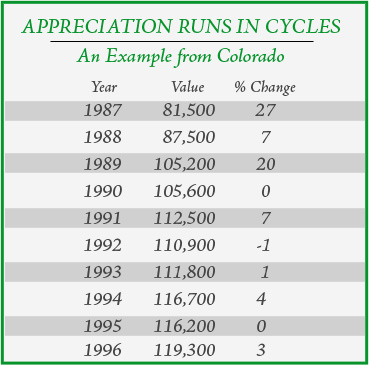

Gary Eldred: Right again. Speculators lose sight of market facts. They think, “The property price went up 15 percent in the past so it will go up 15 percent in the future.” During the last two years, I’ve attended many property shows throughout the world. Hucksters and promoters are pushing properties onto the gullible public with just such an appeal. That’s how bubbles get started.

Rick Dryer: Speaking of bubbles, what do you think of all of this media chatter about the so-called real estate bubble?

Gary Eldred: First, let me back up. My use of the word “bubble” was ill chosen. No property market anywhere that I am aware of shows any evidence of a bubble. Bubbles rarely occur in property markets. The Alan Greenspan term “frothy” better states the case for the priciest property markets around the United States.

Rick Dryer: Frothy? Bubble? What’s the difference?

Gary Eldred: When bubbles burst, little or no value remains. Prices crash by 80, 90, or 100 percent. Stocks experience bubbles, not property.

Rick Dryer: So, what’s “frothy”?

Gary Eldred: Think of a glass of beer. You may get a layer of foam. That’s the froth. Froth makes the glass look fuller than it really is. If you blow the foam away, you still have a glass of beer—just not quite as much as first appeared.

Rick Dryer: In other words, you don’t think property values in our priciest cities are going to crash?

Gary Eldred: No, I don’t. However, just because they won’t crash doesn’t make them a good investment right now. No rational analysis can support further near-term price increases in those markets. People who buy with that hope in mind are placing a speculative bet. Their dreams could come true—after all some people actually walk away from the dice tables in Monaco with their pockets full of chips. But the odds are stacked against that result.

Bubbles rarely occur in property markets.

Rick Dryer: Gary, you mentioned “near term” price increases. Are you saying that over the mid- to longer term, property prices even in the most expensive markets will continue to go up?

Gary Eldred: Absolutely! Rick, I know you’re too young to remember, but this journalistic babble about bubbles and crashes is nothing new. It arises every decade or so. I could cite hundreds of specific “sky is falling,” articles. But here’s just a sampling of

examples that I’ve gathered over the years:

As far back as the late 1940s, journalists warned that, “Houses cost too much for the mass market. At an average price of $8,000, two-thirds of all families are priced out of the market. If you bought your home after the war, you paid too much. The days when you couldn’t lose on real estate are long gone.”

By 1960, the naysayers again fretted. By then the average home price had skyrocketed to $15,000—nearly double the price of a decade earlier. Surely prices are about to collapse, the media warned. By 1970, Business Week complained that at $28,000, “the typical new house is out of reach for most Americans.” The NEA told teachers, “Be suspicious of ‘common wisdom’ that tell you to buy now because home prices are headed even higher.”

Flash forward another 10 years—when California and East Coast home prices jumped above $100,000. A best-selling book of 1980 was titled, The Coming Real Estate Crash.” Then years later (1989), with coastal prices now climbing above $100,000, Harvard economist Gregory Mankiw (later to chair Bush’s II’s Council of Economic Advisors) wrote a widely publicized article that claimed home prices had peaked and would steadily fall 40% by 2005. Media commentators loved it. “Homes are no longer a piggy bank with a white picket fence,” they gleefully reported.

Rick Dryer: That reminds me of Santayana’s familiar line that those who fail to understand the past a re destined to repeat the same mistakes. re destined to repeat the same mistakes.

Gary Eldred: How true. Fortunately, our audience is wise enough to ignore the bubble babble.

Rick Dryer: And they’re now wise enough to see that investors differ from speculators. Either can make money, but but the facts of history favor the investors. |

re destined to repeat the same mistakes.

re destined to repeat the same mistakes.